It was 3.15pm, and my lunch sat on the table, cold and untouched. Midway through a meeting, someone I line-managed said, “Please finish your lunch?” I realised I needed permission from those I looked after to care for myself.

For 20 years, I worked as Simon Sinek (2014) describes: leaders eat last. I believed it. I lived it. I always ate last. Sometimes I didn’t eat at all. My own development, reflection and recovery were always at the bottom of the list. I was rewarded for it because I was visible, high-functioning and high-performing.

I’ve just read Mike Ion’s article Prioritising Wellbeing – a practical guide for school leaders (2025). I stopped at his first point in the list: if you want a culture where wellbeing is valued, you have to start with yourself and model boundaries so others feel able to do the same. It’s not a new idea. Tomsett and Uttley’s Putting Staff First: A Blueprint for Revitalising Our Schools (2020) makes the same case, that sustainable leadership rests on the leader’s own wellbeing. The Department for Education’s School Workload Reduction Toolkit (2018) offered practical steps to make workload manageable. The Teacher Well-Being at Work report (2019) named workload as the top cause of poor mental health.

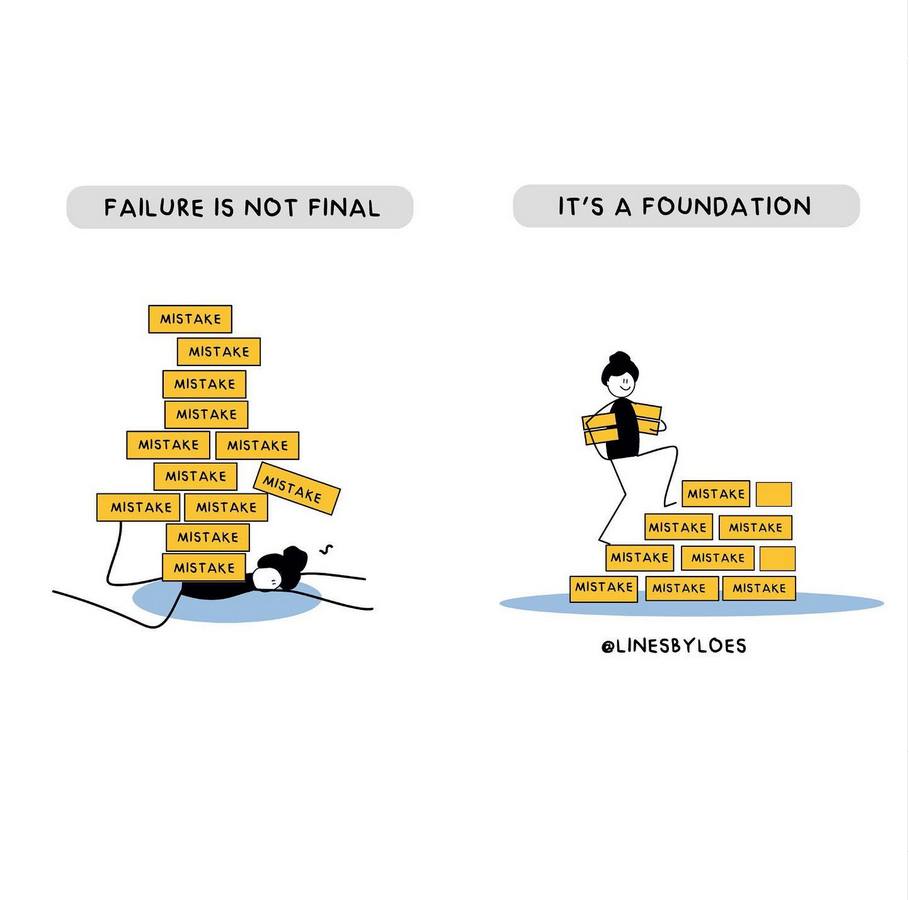

I knew it. I agreed with it. I just couldn’t do it.

The harder truth? If you’re not visibly high-performing, being seen to prioritise your own wellbeing can be resented. It can be a toxic dynamic fuelled by guilt, overwork and the ingrained belief that hours and productivity is the ultimate proof of commitment, even at personal cost. For me, it was part of my own process of institutionalisation as a teacher, something I didn’t even recognise until much later.

Tosca Killoran (2024) writes about the generational shift in teaching: younger teachers often prioritise balance and sustainability, while veteran teachers like me, an elder millennial, were shaped by a culture that valorised sacrifice. That gap can create friction. Killoran’s point is that younger teachers’ emphasis on balance is an opportunity for leaders to re-examine entrenched norms, and to model for staff the same holistic care schools so often promise to students. It also invites us to question what leadership should look like now.

As an Elder Millennial (Shlesinger, 2018), I’ve pushed back against the stereotypes attached to my generation: entitled, fragile, but I recognise how generational framing can shape perceptions of wellbeing. Broad research shows these tensions often reflect career stage as much as generation (Costanza et al., 2017), yet the effect is the same: a system that rewards overextension and mistrusts visible rest.

This year, for the first time in two decades, I’m standing outside the back-to-school rush. This break isn’t a hiatus from leadership. It’s the breathing space I need to practise the systems and boundaries I couldn’t make stick before, so I can lead sustainably, for myself and others in the future.

Help me out with your wisdom: What does it take for you to lead in a way that sustains both you and those you serve?

Leave a comment